Remembering both my grandmother, Mary Bradford, and Low’s Mimi Parker — two women who operated unconventionally within their shared faith — through the lens of challenging music.

My grandmother, Mary Bradford — writer, poet, editor, and teacher — also happened to arguably be one of the greatest Facebook commenters of all time. A few years ago, I shared a YouTube link on Facebook to the song “Heaven” by the Walkmen, calling it “triumphant,” “epic,” “magnificent,” and “a top 5 song of the decade.” The song’s main refrain implores the listener to “Remember, remember / all we fight for.” My grandma commented:

“EXCUSE me — what am I to remember? Being attacked by this noise?”

In classic Mary fashion, she had responded with a takedown as epic as the song itself, eviscerating it in just 12 words.

My grandmother’s comment surprised me. I wouldn’t characterize “Heaven” as a challenging or inaccessible song. After all, it did soundtrack the finale to one of the most popular TV shows of the last decade, How I Met Your Mother, so it has the potential for mass appeal. But I guess, sometimes to the ear of a listener, a song’s inherent beauty or power might fail to emerge from behind a particularly loud guitar, a strained vocal, a deluge of sound effects.

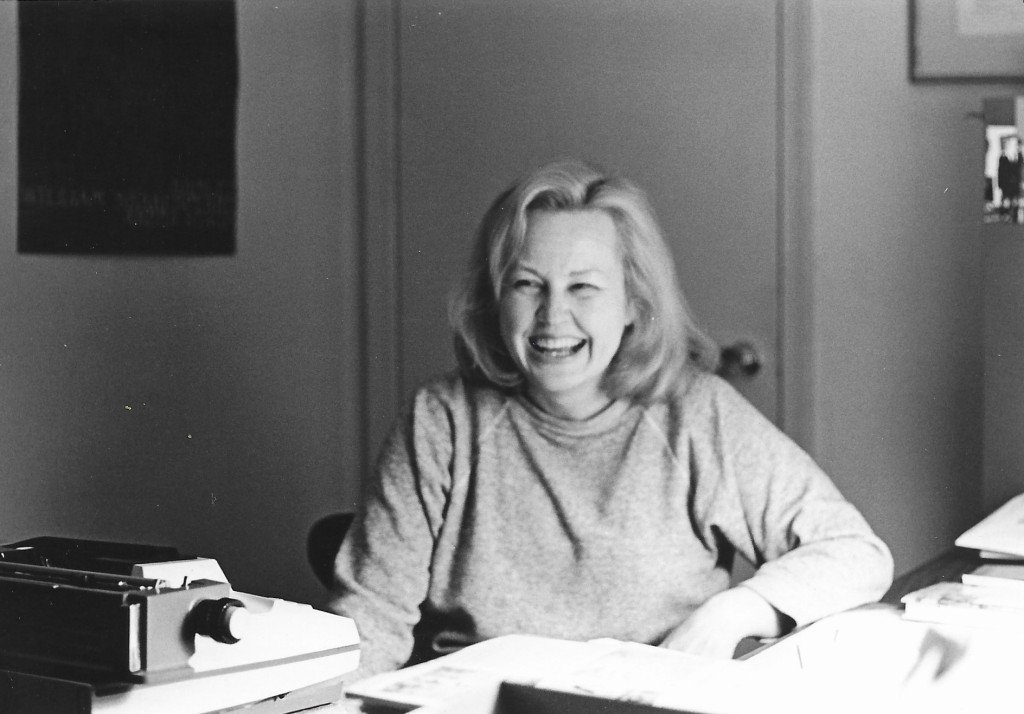

Mary, or “Nama” as she was known to my cousins and me, passed away this month at the age of 92. It’s sad to be without her, but I am heartened by the fact that she lived a full and meaningful life, and I’m incredibly grateful for the 33 years I did have with her.

Notwithstanding her distaste for what I considered to be a beautiful song, in other, more important contexts, Mary Bradford knew how to exist in difficult environments. She made a habit of digging into and reveling in the beauty sometimes hidden in those environments. As a lifelong intellectual and feminist in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (widely known as the Mormon or LDS church), she often seemed like a walking contradiction to more traditional, conservative members of the faith. (Her life and work were expertly captured in Peggy Fletcher Stack’s Salt Lake Tribune obituary.)

“Some people thought I was a little uppity,” Mary said later on in life. “I should’ve been having more kids instead of trying to write things, you know. I loved the church… I was happy in the church.” Despite operating outside of the traditional norms of the church, she still made a place for herself within its literal and figurative walls. In one of her essays, she wrote, “I formed the notion that the church was ‘my’ church, that it belonged not only to its leaders, but also to me.”

Already a writer, poet, editor, and teacher, Mary served as the editor of Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought in the late 1970s, an independent publication that, at times, generated controversy among church members by publishing scholarly articles that addressed progressive topics such as the place of feminism within the church. She would work with the Dialogue staff to compile the next issue in the downstairs of their house in Arlington, Virginia, while her husband, Charles (“Chick”) would conduct business related to his position as bishop of the local ward in the upstairs of their house. Both provided leadership and engagement with Mormonism, but it was wryly acknowledged within the family that the authorized, church-sanctioned version occurred upstairs and the more tendentious version took place in the less exalted downstairs realm.

In 2015, Mary published a collection of the personal essays she had written throughout her life. In Dialogue’s review of the collection, Joey Franklin aptly summed up my grandmother’s worldview: “[Bradford’s essays read] as a reminder that authenticity depends a great deal on one’s willingness to engage with all aspects of one’s self, and that between the poles of sanctimony and cynicism, there is a hopeful place where art and faith can thrive, not in spite of, but because of each other.”

________________________

My grandmother’s death happened two days after that of Mimi Parker, a core member of Low, one of my favorite indie bands. She passed away at the age of 55 from ovarian cancer. At first glance, there doesn’t appear to be much in common between Parker and my grandma, but when you think of them as Mormon women living unconventionally within their worlds, the similarities start to click.

Mimi (pronounced “MIM-ee”) Parker, and her husband Alan Sparhawk, met in elementary school in northern Minnesota and started dating in high school. Sparhawk grew up Mormon, and actually attended BYU for a year before returning to Minnesota with Parker, who joined the church as an adult. Sparhawk and Parker moved to Duluth and formed the band Low in the early 1990s, serving as the band’s main members for almost 30 years — Sparhawk on guitar and vocals, Parker on percussion and vocals — along with a rotating cast of bass players. They toured the world and gained critical acclaim, but always returned to their humble home base, raising two kids together and growing their deep roots in Duluth.

Parker’s death hit like a ton of bricks, as anyone’s would at her relatively young age, but especially since she was fairly quiet about her diagnosis. She was mourned widely by the music community, including by Robert Plant of Led Zeppelin, Jeff Tweedy of Wilco, Justin Vernon of Bon Iver, and Carrie Brownstein of Sleater-Kinney.

Though Low’s sound evolved over time, the foundation of their music was always Parker and Sparhawk’s entwined, lockstep harmonies. When it comes to vocal harmonies, Low is up in the rafters with the likes of Crosby, Stills & Nash, the Beach Boys, the Mamas & the Papas, and the Beatles. On “What Part of Me,” perhaps my favorite Low song, no note or sound is out of place.

Some singers need the help of a studio to tune their voices, but not Alan Sparhawk and Mimi Parker. When they performed live, their vocals were just as powerful as on their records, if not more so.

Low released 13 albums over the course of their career, and on the group’s last two projects, their sound took a much more distressed turn, as they dialed up the distortion and ran their instruments through filters to the point of making them almost unrecognizable. On the most recent album, last year’s HEY WHAT (my favorite album of 2021), they excelled at letting the beauty of their harmonies and songwriting shine through the static.

If my grandmother didn’t care for the alleged “noise” of “Heaven” by the Walkmen, I can guarantee you she would not take a liking to HEY WHAT. Take “Disappearing” as an example. I think it’s an absolutely gorgeous song, but you might think I’m crazy. I can hear the skepticism now — “How can a song that sounds like a Boeing 777 pulling off a runway be construed as ‘gorgeous?'” It’s because through it all, the backbone of the song is still Sparhawk and Parker’s vocals. The onslaught of processed airplane-hangar guitars that enter halfway through are accompanied by the duo’s celestial harmonies ascending, all amping up to form a cathartic, satisfying climax that makes my hairs stand on end.

“More”, the album’s penultimate track, is an even more extreme example of beauty becoming disguised as it’s caked with production. It’s a song “dominated by a ragged, glitchy, all-consuming guitar riff,” as I wrote last year, naming it the third best song of 2021. “Parker’s hypnotic vocal harmonies make it more than just a droning hard rock song — it’s an alluring, transportive experience… [‘More’] deftly juxtaposes aggressive noise with striking beauty.” In Rolling Stone’s review of the album, Kory Grow summed it up best: “Few bands have stared into the abyss quite like Low, parsing the frailty of the human condition, testing listeners with glacially slow tempos, encrusting beautiful melodies in sparse textures or dissonance. And no band has done so with the same beatific grace as Low.”

Low’s more recent inclination to fill their songs with noise and distortion makes the moments of pure beauty all the more impactful. The process of unearthing these moments as you listen, and feeling their sweet release amid the chaos, is immensely rewarding.

My grandmother would have hated HEY WHAT, but the key to loving the album is not dissimilar to the central tenet for how she lived her life — mining for beauty within the noise.

________________________

Mimi Parker always felt like a real person — unassuming, humble, authentic, just like my grandmother. Parker was a midwestern, Mormon mom with a passion for baking, who happened to also possess a subtly stunning voice and use it in a creatively adventurous, renowned indie rock band. Mary Bradford was a small-statured Mormon mom and grandma who loved the color purple and reveled in everything her progeny did, who also happened to be a prominent and influential writer and thought leader for many church members. They both had creative sparks — Parker through music, Mary through essays and poetry. They both seemed demure, but never hesitated to tell it like it is. If we went out to eat and my grandma wasn’t a fan of the food, make no mistake, she would say so. And Alan Sparhawk, Parker’s husband and bandmate, said of Parker, “She did not suffer boring music. She did not suffer mediocrity.”

It’s not outlandish to think that traditional Mormonism doesn’t necessarily mesh well with intellectualism and exploring challenging ideas (in the case of my grandmother), nor hitting the road to play and record indie rock music (as Parker did). But Mary and Mimi both shared a view that the two seemingly incongruous worlds they each embraced were not only not at odds, but both of them were incredulous at the idea that they couldn’t exist and flourish in both worlds.

It came naturally to Mary to be both an intellectual writer and a Mormon. “In the mind of some, piety and publishing don’t mix—especially independent, scholarly publishing in a church context,” she wrote. “But our response was: They do too mix!”

To Parker, she openly wondered earlier on in her Low career why being Mormon was considered such a peculiarity: “I wonder where the Mormon fascination comes from? In England, that was all any journalist could talk about. And it’s starting to become a bigger deal over here [in the U.S.]. But we don’t get particularly upset about it. People just like to say that we’re this quiet band from Minnesota that is two-thirds Mormon, but hey, you know? We write some songs, too.”

________________________

Whether Parker felt it or not, there is no getting around that being a practicing Mormon in the music business is extremely anomalous. Brandon Flowers is not the norm. I almost teared up while reading the Minnesota Star Tribune and Duluth News Tribune’s accounts of Parker’s funeral, held at the Mormon church in Duluth, because of how familiar the little details of it sounded to me, also a lifelong church member.

Granted, the funeral sounded as familiar as it could be while having dozens of acclaimed musicians sitting in the pews alongside members of the Duluth Ward congregation, but still… a printed recipe for Parker’s famed cream puffs was included with the programs, with some of those cream puffs made and provided by Relief Society members for the service; a photo of the aforementioned rotating cast of bass players in what is very clearly a Mormon church foyer; a tale from David Gore (the Star Tribune labeled him as the “church president,” so knowing that wasn’t true, I verified that he was the Duluth stake president) about the first day he attended church in Duluth when in town for a job interview and hearing Parker and Sparhawk singing “Silent Night” from the pulpit; “How Great Thou Art” being mentioned as one of the hymns played; post-service refreshments in the cultural hall.

If these sound like mundane details, maybe they are, in a vacuum. But it’s not often you hear about an indie musician’s funeral containing elements like these. It’s poignant for me, as both a Mormon and a big fan of Low.

Parker was open about her Mormonism, but never put it front-and-center. Low’s songs often touched on spiritual themes, but were never blatant or preachy — they simply reflected the couple’s own experiences with spirituality and religion. On “Holy Ghost,” Parker examines her inner turmoil and the peace that a spiritual being can bring: “Some holy ghost keeps me hanging on, hanging on / I feel the hands, but I don’t see anyone, anyone / Feeds my passion for transcendence,” Parker sings.

“Now I don’t know much, but I can tell when something’s wrong, and something’s wrong. But some holy ghost keeps me…” She doesn’t finish her sentence at the end, tailing off into “oohs,” but the warmth of the closing chords gives the impression that this holy ghost did its job as a comforter. In an interview on SHEROES Radio, a show that focuses on spotlighting women in music, Parker discussed finding solace in prayer in light of her cancer diagnosis.

Ultimately, especially going through the cancer diagnosis, I really relied heavily on [spirituality]. I would pray, and I really felt like I did receive comfort, and I received help because of those prayers. And I had so many people — friends that were close to me — that were praying for me every day. And I really feel like that made a huge difference.

It seems kind of magical in a way, and it kind of is. But I think we need some magic. We need some magic in this life.

________________________

It’s heartening to see Sparhawk and Parker as examples of well respected and clearly progressive members of my church who lived authentically. At Mary Bradford’s funeral, authenticity was a common theme as well. If she had decided to suppress her personality and beliefs to better fit in with the majority of her fellow church members, then she would have lost the uniqueness that made life meaningful not just to her, but to others on the margins who looked up to her and respected her. She was an anchor for her peers and readers who also didn’t want to follow the status quo. To many, that is her most important work — that she made others’ lives feel valid, because of how she chose to live her life. She impacted others just by being herself.

Shortly after Parker’s death, Sparhawk posted a tweet from Low’s account announcing her funeral.

It was simple, but it hit me hard —a tweet mentioning future plans at the LDS church, right before advocating for equal rights and justice, and being unapologetic about both. It’s something my grandmother would have done. Traditional norms can be hard to navigate when you feel like an outsider, but to Mimi Parker and Mary Bradford, sometimes it’s worth being “attacked by the noise” to unearth the beauty lying just beneath it.

________________________

Book References

Mary Bradford, Mr. Mustard Plaster and Other Mormon Essays, p. 36 & 60.

Other Reading/Listening

My favorite Low songs (Spotify playlist)

Low’s La Blogotheque performance

Low’s NPR Tiny Desk performance

“One Tree,” poem by Mary Bradford

Mary Bradford’s obituary

Salt Lake Tribune’s remembrance of Mary Bradford

Duluth News Tribune’s account of Mimi Parker’s funeral

Slate’s rememberance of Mimi Parker

Thanks to Taylor Parsell for her editing help and added insights.