Discussing the band’s pioneering legacy; their position in heavy metal and hard rock (and my relationship to both genres); covers of Black Sabbath songs from unexpected sources; and then wrapping up with their 15 best songs.

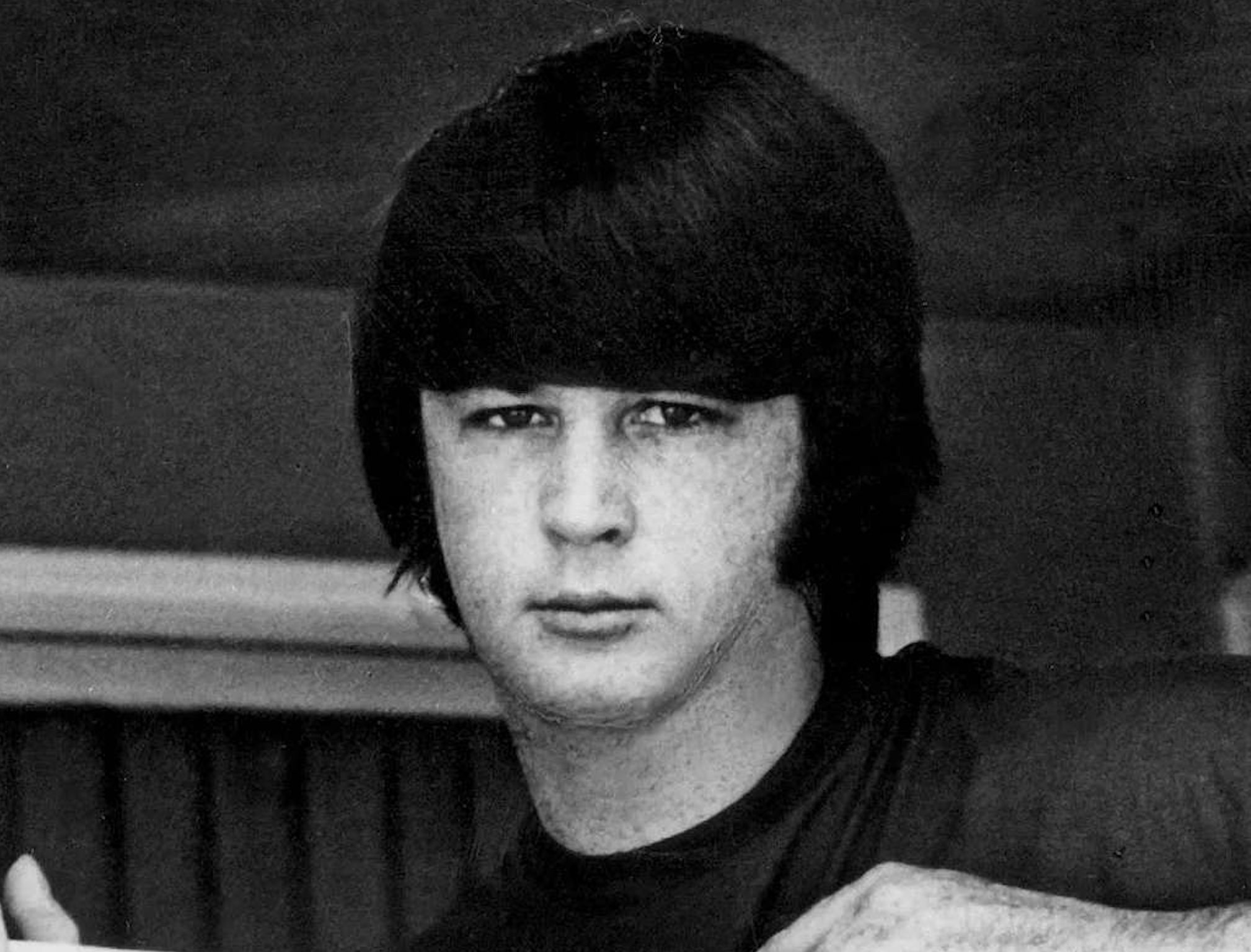

(Photo courtesy of Billboard, page 7, 18 July 1970)

Black Sabbath’s Pioneering Legacy and Their (and My) Relationship to Heavy Metal

Last month, Ozzy Osbourne finally succumbed to the death he had eluded for so long, at the age of 76. Ozzy became a cultural phenomenon outside the realm of music — a popular reality show and biting the head off of a bat will do that to you. But I couldn’t care less about any of that. The only thing I really care about is the music, because it was innovative, it was influential, and it was just plain good.

Since his passing was announced, I’ve been blasting Ozzy-era Black Sabbath non-stop, and it got me thinking: whenever I think of musical artists that were “ahead of their time,” it’s not Bowie, or the Kinks, or the Velvet Underground that come to mind first — though they all certainly qualify. The first group I think of is Black Sabbath.

No one sounded like them. Yes, there was Cream, Jimi Hendrix, Led Zeppelin, Blue Cheer, bands making a heavier and more distorted form of blues rock, but no one had turned the dials up on that formula and combined it with the sense of dread that Black Sabbath did. The riffs were thick and chewy, the lyrics were haunting, and Ozzy’s vocals were primal. He wasn’t the most technically proficient singer, a la Robert Plant, but his voice had a gravitas that drew you in, excited you, scared you.

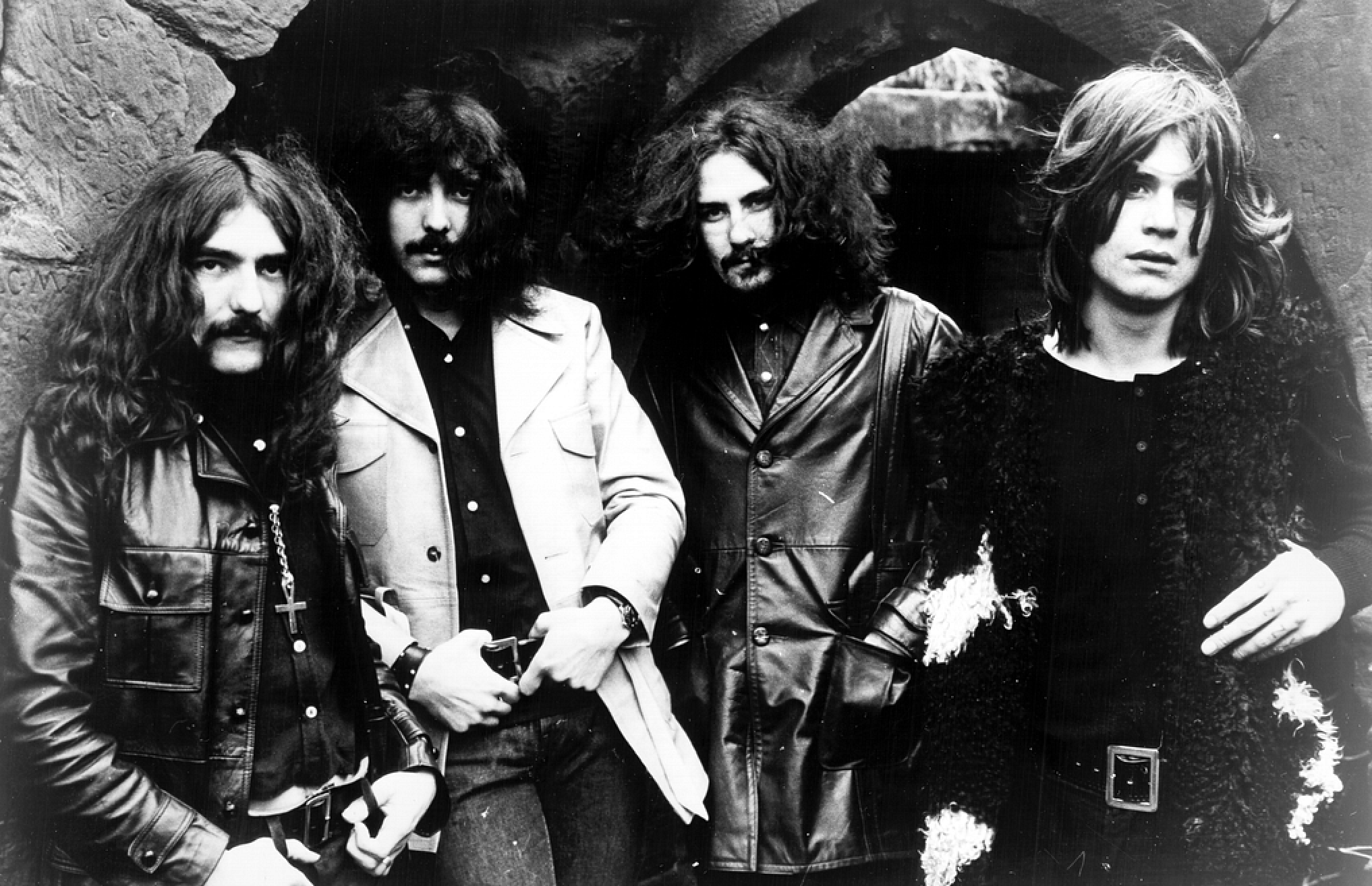

Obviously you could hear the horror in Sabbath’s music, but you could also see it. I mean, just look at the mustaches and the crosses. Look at Ozzy while he belts “War Pigs.” And look at their debut album cover! I can’t believe the label let them use that cover. Legitimately scary.

Black Sabbath’s frightening debut album cover (1970)

They were true pioneers, tapping into a sludgy doom that people didn’t even know was possible yet. And it resonated, big time. Despite critics panning the band (like Lester Bangs of Rolling Stone calling the music “claptrap”), album sales were huge. Fellow outcasts, weirdos, and the working class felt Sabbath’s music within their bones. Rob Halford, frontman for Judas Priest, one of the many heavy metal bands indebted to Black Sabbath, put it best. “They were, and still are, a groundbreaking band. You can put on the first Black Sabbath album and it still sounds as fresh today as it did 30-odd years ago. And that’s because great music has a timeless ability: To me, Sabbath are in the same league as the Beatles or Mozart. They’re on the leading edge of something extraordinary.”

My teenage friend group loved heavy metal, and even played in a Metallica-inspired metal band in high school called Revelation. While I appreciated the genre, and had songs that were favorites of mine — Metallica’s “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” Motörhead’s “Ace of Spades,” pretty much anything by the aforementioned Judas Priest — I could never fully sink my teeth into lots of the most popular forms of metal, especially thrash metal like Slayer, Pantera, or Anthrax. The musicality was impressive, but it only spoke to me in bits and pieces.

So why did I adore Black Sabbath (and still do), when they were the originators of metal, a genre I’m only mildly interested in? It’s because their brand of metal was still in its infancy, still yet to fully branch off of “hard rock,” a genre I am passionate about. Metal hadn’t evolved into the thrashing, head-banging ecosystem it is today. That grey area between metal and hard rock hits a sweet spot for me — less pummeling, but still full of heavy riffs, booming drums, and howling vocals. Judas Priest’s radio-friendly hits often fit into that grey area, along with bands like AC/DC, Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple, Heart, and Van Halen.

I would argue that Black Sabbath, despite being the first metal band, actually align more closely with “hard rock” than “metal,” particularly in those ’70s-era Ozzy days (as opposed to the more full-blown metal they would embody after firing Ozzy and employing singers like Ronnie James Dio in the ’80s). Their self-titled debut (the one with the creepy album cover) has the bluesy, harmonica-laden “The Wizard,” as well as “N.I.B.,” which takes the psych-rock sound of Cream’s “Sunshine of Your Love” and makes it nastier. Then they released Paranoid — the platonic ideal of “hard rock” (also their best work and quite possibly a top-ten-all-time album for me). Tony Iommi’s riffs are gigantic throughout, but they’re also chunky and tactile, still coated in the blues in a way that most metal is not. Bill Ward’s drum fills are too dry, and Geezer Butler’s melodic bass is too vibrant to be considered metal.

After those first two albums, flickers of metal begin to surface, but those flickers are channeled through a hard rock filter, which is just how I like my metal. It’s thrilling to listen to Master of Reality, Vol. 4, and Sabbath Bloody Sabbath, and get little tastes of the metal that would sprout forth a decade later — the filthy midsection of “Sabbath Bloody Sabbath,” the trudging doom of “Into the Void”, the inevitable gallop of “Supernaut,” or the relentless onslaught of a riff on “Children of the Grave.”

The fact they were making songs as heavy as “Children of the Grave” as early as 1971 just blows my mind. Only ten years earlier, the heaviest rock and roll in existence was surf rock. In the earliest years of the 1960s, bands like the Beatles and the Kinks were barely blips on the radar. The doom and gloom of Black Sabbath couldn’t have even been conceived in anyone’s wildest imagination.

Their impact was immense, their level of “metal” was perfect, and their songs were excellent.

Unexpected Black Sabbath Covers

Black Sabbath is obviously tremendously influential for any metal band that has existed, but their reach was wider than you might think. Here are a few great Sabbath covers from non-metal artists.

The Cardigans: “Sabbath Bloody Sabbath” / “Iron Man”

Swedish pop rock band The Cardigans, of “Lovefool” fame, covered quite a few Sabbath songs, including an airy take on “Sabbath Bloody Sabbath,” and a groovy “Iron Man.”

Charles Bradley: “Changes”

Charles Bradley, the soul singer who channeled James Brown so effectively that he impersonated him on stage at local clubs, miraculously got his music career off the ground in the 2010s, when he was already in his 60s, before passing away in 2017. The original “Changes” was already an outlier in Sabbath’s catalog — a maudlin ballad with nothing more than piano, mellotron strings, and bass. Its minimalist nature made it a perfect blank canvas for Bradley to turn it into a completely natural sounding, 1960s-style rhythm & blues track.

T-Pain: “War Pigs”

T-Pain covered Black Sabbath. Yes, you read that right. T-Pain. The 2000s R&B hitmaker lends his autotune-less voice to a straight, mostly unchanged, live rendition of “War Pigs,” and kills it. Absolutely kills it. Ozzy himself said it was the “best cover of ‘War Pigs’ ever.”

The 15 Best Black Sabbath Songs

Honorable Mention: “Killing Yourself to Live” (Sabbath Bloody Sabbath, 1973)

15. “Junior’s Eyes” (Never Say Die!, 1978)

“Junior’s Eyes” is from Ozzy Osbourne’s last album with Sabbath before the band fired him for his alcohol and drug use (though the other members didn’t have much of a leg to stand on in that department). Never Say Die! is often maligned as being below the standard of their early albums, and it is, but there are some gems, especially the groovy, bass-heavy, hard rock masterpiece “Junior’s Eyes.” It was never a hit, but it should have been — that soaring chorus would fit right in on classic rock radio.

14. “Tomorrow’s Dream” (Vol. 4, 1972)

If you want a short, straightforward Sabbath song, with a fat, simple riff, then “Tomorrow’s Dream” has you covered.

13. “After Forever” (Master of Reality, 1971)

Black Sabbath were often unfairly maligned for being Satanists, but the band members were actually more Catholic than you would expect, and never more overtly so than on “After Forever.” Just look at these lyrics: “Perhaps you’ll think before you say / ‘God is dead and gone’ / Open your eyes, just realize / That He is the one.” Doesn’t really sound like a Satan-worshipper to me! But that doesn’t really have any effect on my opinion of the song. I like it because the bass weirdly sounds like “Paperback Writer.”

12. “The Wizard” (Black Sabbath, 1970)

Led Zeppelin weren’t the only ones singing about Lord of the Rings — bassist and lyricist Geezer Butler says he wrote this about Gandalf. Also, unless my research failed me, this is the only song on Sabbath’s first four albums where Ozzy played an instrument — that bluesy harmonica.

11. “Planet Caravan” (Paranoid, 1970)

Congas, flute, piano — not instruments you usually hear from a supposed “metal” band, but “Planet Caravan” puts other underappreciated dimensions of Black Sabbath on full display. Despite no riffs to be found, the jazzy psychedelia here still boasts plenty of Sabbath’s spooky aura.

10. “Supernaut” (Vol. 4, 1972)

Whenever “Supernaut” comes on, it’s literally impossible not to ferociously head-bang. It just rocks too hard.

9. “Jack the Stripper / Fairies Wear Boots” (Paranoid, 1970)

Anyone who wants to slag on Ozzy’s talents should just listen to his chilling vocals on the swinging “Fairies Wear Boots.” He recounts the tale of how “suddenly, [he] got a fright,” and the terror is right on the surface. Bill Ward went crazy on those drum fills too.

8. “Into the Void” (Master of Reality, 1971)

Of the various subgenres of metal, my favorite is probably “doom metal,” characterized by slow, thick, down-tuned guitar riffs. “Into the Void” is the quintessential doom metal prototype. James Hetfield, guitarist for Metallica (notably, more of a thrash metal than a doom metal band), says this is his favorite Sabbath song.

7. “Snowblind” (Vol. 4, 1972)

The most blatant “cocaine” song in their catalog — just in case you find “Feeling happy in my vein / Icicles within my brain” to be ambiguous, Ozzy helpfully whispers “cocaaaiiine” to get the point across. “Snowblind,” and all of Vol. 4, has a sandpapery, treble-heavy, exciting guitar sound — I can hear the beginnings of grunge, can picture Kurt Cobain hearing “Snowblind” and trying to get that sound on Nevermind.

6. “Sweet Leaf” (Master of Reality, 1971)

It’s fitting to follow Sabbath’s most blatant “cocaine” song with their most blatant “marijuana” song. Tony Iommi’s immortal reefer-laden coughs are followed by one of the sickest riffs you can imagine, as Ozzy wails “ALRIGHT NOW!” and “I LOVE YOU!” to his beloved sweet leaf.

5. “N.I.B.” (Black Sabbath, 1970)

As I alluded to before, the “N.I.B.” riff is like if “Sunshine of Your Love” had an evil twin. When you combine Geezer Butler’s absolutely filthy bass solo opening with Ozzy’s conviction and that guitar riff, it’s hard to find a more hair-raising song anywhere.

4. “Sabbath Bloody Sabbath” (Sabbath Bloody Sabbath, 1973)

I mentioned this song earlier, when talking about the “flickers of metal” in Sabbath’s early music. I just can’t believe how a song from 1973 can be this heavy in the middle section (which you can hear at 3:19 in the track). But the rest of the song is amazing too — Ozzy’s howling over the main riff, followed by an almost sweet and pensive acoustic section. And then, there’s that disgusting mid-section (complimentary).

3. “Iron Man” (Paranoid, 1970)

If we’re just ranking Tony Iommi’s greatest guitar riffs, “Iron Man” ranks at #1 (“Paranoid” is #2, “Supernaut” is #3, “Into the Void” is #4, and “Children of the Grave” is #5). In fact, “Iron Man” might have the greatest riff ever created by anyone — apologies to Jimmy Page, Keith Richards, Angus Young, Kurt Cobain, Nancy Wilson, etc. What’s funny is that this song has at least 4 incredible riffs throughout its runtime — Iommi must have said “let me just put everything in here and make it the best electric guitar song ever.”

2. “Paranoid” (Paranoid, 1970)

The story has been told a million times before, but “Paranoid” was an afterthought, written in about a half hour when they needed to fill 3 minutes of empty time on the album that would eventually also be called Paranoid. Greatest afterthought of all time? “Paranoid” is a tightly-wound burst of energy — hard, fast, and insanely catchy, with all four band members firing on all cylinders.

1. “War Pigs” (Paranoid, 1970)

My whole arm has been hurting for a month now, ever since Ozzy’s death, because I can’t stop listening to “War Pigs,” which means I can’t stop vigorously air-guitaring every note and air-drumming every beat. “War Pigs” is a masterpiece. Every piercing riff, every bass groove, every drum fill, and every haunting wail is so freaking satisfying and perfect. While the hippies were preaching peace and love in the face of the Vietnam War, Sabbath were more accurately channeling the horrors of war and more bluntly calling out the perpetrators: “Politicians hide themselves away / They only started the war / Why should they go out to fight? / They leave that role to the poor.” As relevant today as it has ever been.

If you want to hear these 15 tracks, plus a bonus 15 more, enjoy a Spotify playlist of the 30 best Black Sabbath songs: